By Digital Archivist, Emma Hancox

As well as digitising two dimensional materials, at the University of Bristol we have been experimenting with three-dimensional scanning methods. We are actively engaged in digital preservation and the creation of 3D scans creates its own set of challenges. In terms of access, we have started working on ways of increasing interaction with the 3D models we create breaking down barriers, giving our collections a wider reach and unlocking their potential in the long-term.

In June 2021 we used 3D scanning methods to image the Blandford collection of antiquities which is housed in the University’s Department of Anthropology and Archaeology. The collection was donated to the University by Dennis Blandford, a retired classics teacher, and incudes Greek and Roman artefacts such as pottery, terracotta figures, roof tiles, bracelets and pins.

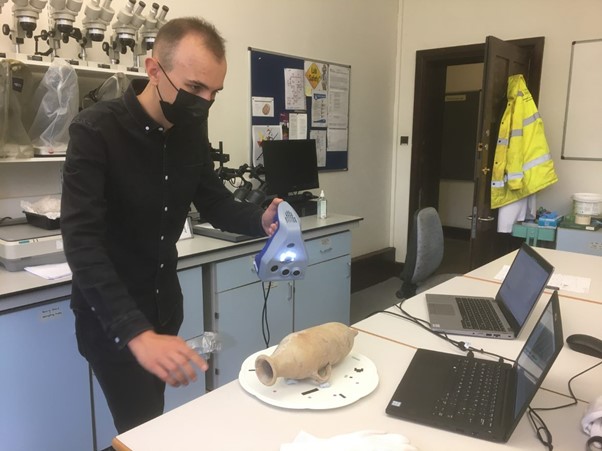

It took three members of staff six days to scan around half of the collection prioritising in-demand and unusual objects. The team used a hand-held scanner called an Artec Space Spider. At this stage the work involved data-capture and upload of the scans to a cloud server. Post-processing tasks such as reconstructing 3D depth took a further three weeks to complete.

During the scanning stage the team found that scanning objects with reflective surfaces was a challenge because they reflected the light from the scanner. Larger objects were easier to scan than smaller ones. While scanning, a cake-stand with stickers placed in a non-repeating pattern was used so that the objects could be rotated while scanning. The stickers helped the scanner identify the rotation. A lesson learnt during the processing stage was that it was difficult to auto-align objects with plain sides because there were no distinguishing features to base the alignment on.

Of course, the process of 3D scanning creates a set of digital assets that need to be preserved in the long-term. The 3D models were stored in the Wavefront OBJ format which was selected because it is open source, widely used and is considered to be an acceptable format for scanned 3D objects by the Library of Congress in their recommended formats statement. Alongside the .obj file a .png file holds the colour and texture information and an .mtl file contains information about how the textures should be applied to the 3D object. The three files are required to view the 3D model. Preservica (the digital preservation system we use) supports the format identification, validation and rendering of Wavefront OBJ with associated .mtl and image files such as .png and we are in the processing of testing the ingest of 3D scans to the system.

As well as making the 3D models available in data.bris.ac.uk we wanted to explore ways of allowing users to interact with the 3D models in a virtual reality environment. A virtual museum environment was coded using ValveHammer and shared via the SteamCommunity. It allows the user to view a clipboard with a list of boxes on it, select a box and view the items from the Blandford Collection within it. The items can be sorted, shrunk or enlarged and taken to a returns table when finished with.

The Blandford Collection is primarily used for teaching and the creation of the 3D models and VR environment will allow more students to connect with the objects. It also enables wider access to the collections from users based anywhere in the world. In the future we would like to have a virtual museum space where we can hold a series of virtual exhibitions using a variety of 2D and 3D scans. We envisage that these could be curated by students as part of their university courses.

One of the challenges we are yet to explore is how we might approach preserving the 3D museum environment we have created and this is something we would like to investigate in the future.

Thank you to my colleagues Stephen Gray, Catherine Dack and Sam Brenton who carried out this work and explained their processes to me.